|

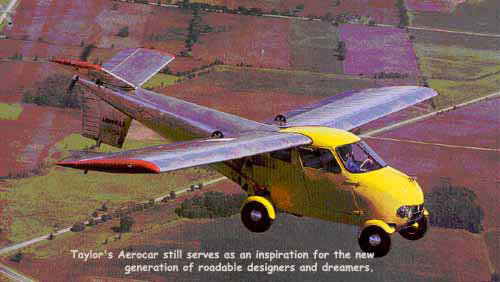

Molt Taylor's Aerocar still serves as an inspiration for the new

generation of roadable designers and dreamers.

The Aerocar flight instructions went something like this: "It's easy. It

practically flies itself. I'll tell you what to do as we go along."

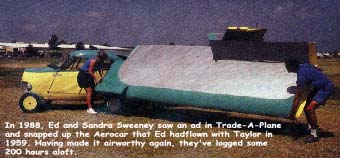

In the summer of 1959, Moulton Taylor, with a little time on his hands and

the zeal of a missionary, was seeking another convert. He'd given his student, a

recent high school graduate named Ed Sweeney, the use of his Longview,

Washington sod runway to fly radio controlled model aircraft.

But this was no model. Nor was the four-wheel vehicle Sweeney steered

down the runway strictly an airplane. Had Taylor stripped the craft of its wings

and tail section, Sweeney could have signalled a couple of turns and driven into

town, as Taylor sometimes did, on a head-turning jaunt to the grocery

store.

With Taylor at his side, Sweeney left the ground at about 55 mph. "Okay,

we're high enough," said Taylor. "Let's make a turn." Sweeney dialed the

steering wheel and the Aerocar quickly responded. The landing was equally

smooth. "Just drive it down the runway," said Taylor, "and when you're ready to

stop, simply step on the brake." Sweeney enjoyed his brief drive in the sky, but

his encounter with the Aerocar was not love at first flight. "It didn't mean all

that much to me at the time," The media has always loved flying cars,

particularly Molt Taylor's Aerocar. Taylor, the dean of roadable airplanes,

devoted most of his adult years to making the Aerocar a reality. The Aerocar IV,

is based on a Geo Metro.

Aviation historians consign the flying automobile to the oddity hangar, a

niche reserved for the Spruce Goose, the autogiro, and other noble though quirky

experiments. But if a flying car has yet to attain success, the idea of one is

still very much alive.

The thinking of the time was that there was a need for such a dual-purpose

vehicles. "Not only are roadways more congested with each passing year, but the

airlines' hub-and-spoke system has, over many mid-length routes, actually

increased travel times. But that's only part of what inspired flying car

designers. As Chuck Berry sang in his 1956 recording "You Can't Catch Me," the

ability to transform a car into a plane is liberating-freedom at the push of a

button:

I bought a brand new Aeromobile.

Custom made, 'twas a flight de

ville.

With a powerful motor and some highway wings,

Turn offthe button

and you will hear her sing.

Now you can't catch me. Baby, you can't catch

me.

'Cause if you get too close, you know I'm gone

......Like a cooool

breeze.

But the flying car remains a romantic vision, a kind of aeronautical

mirage. The challenges of building one are perhaps exceeded only by the

challenges of selling it. Because a vehicle worthy of both land and air has

compromise written all over it, the technical challenges are numerous. The

common elements are few- fuel tank, steering wheel, passenger and baggage

compartments, wheels, and engine. For flight you need wings, ailerons, a

horizontal stabilizer, a vertical tail, rudder, elevators, and a propeller, none

of which has any business on a car. For the road, you need a drive train and

bumpers, not to mention rear-view mirror and, nowadays, catalytic converters-all

dead weight in the air. The history of flying cars can be written in a single

sentence: As airplanes, they've all been too heavy.

Still the quest goes on with imaginative and divergent approaches, which

range from simple kit-built vehicles to a James Bond-like concept -with sleek

lines and telescoping wings. (Even 007 himself hasn't seen a real flying car.

The one in The Man With the Golden Gun was a static model "flown" by Hollywood

special effects.).

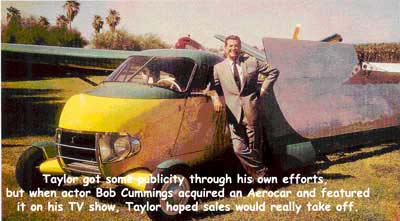

One of the most credible still belongs to Molt Tavlor. Taylor got some

publicity through his own efforts, like storing the Aerocar in his garage. When

actor Bob Cummings acquired an Aerocar and featured it on his TV show, Taylor

hoped sales would really take off.

Taylor was revered as a kind of patron saint of the flying car. "Oh, I had a

ball," he says with a high-pitched chuckle. Visitors to his home in Longview

would hear his string of stories-like the time he got a speeding ticket in

Florida while driving an Aerocar to an auto show. And once, while delivering an

Aerocar to pilot and actor Bob Cummings, Taylor made a spur-of-the-moment stop

at an Earl Scheib paint shop. After verifying that, yes, the $39.95 two-color

rate was good for any car, Taylor had them match the yellow and green colors of

NutraBio, the vitamin company that sponsored"The Bob Cummings Show," on which

the Aerocar would thereafter regularly appear in the early 1960s. Taylor himself

was on TV countless times. His favorite appearance? The time he drove the

Aerocar onto the stage of "I've Got a Secret" and, with the help of an assistant

and while answering the questions of the blindfolded panel, went about the

car-to-plane conversion. Three minutes later there was an airplane sitting

there.

Taylor was a gifted aeronautical engineer, "crazy about airplanes" from

adolescence. In 1942, as a Naval reservist, he became the first person to

successfully "fly" a surface-to-surface missile to its target, and the following

year, as a lieutenant commander, he headed the project that produced the first

generation of cruise missiles. His resume also includes homebuilt aircraft Re;

the Coot, an amphibious "floatwing" plane, and the Imp and Mini-Imp, two types

of one-place sportplane with an inverted V-tail. An early version of an Imp

helped launch his flying car quest. In 1946, while shopping for a plant in New

Castle, Delaware, to build an amphibious sportplane he was then calling the

Duckling, Taylor bumped into Robert E. Fulton Jr., soon to be heralded in Life

magazine for his flying car, the Airphibian.

Taylor was impressed with Fulton's incarnation of a winged automobile as

was the Civil Aeronautics Administration, which later awarded it a type certificate, the

first of only two flying cars ever certified for production (the other was

Taylor's Aerocar).

I saw it fly and watched him leave the wings and tail behind

and drive off in the car," says Taylor. "I thought that a good idea. But I can

do better." Taylor reasoned that if the whole idea of a flying car was that it

would give you the freedom to go where you pleased when you pleased, then

leaving behind the flight components was a less than optimal engineering

solution. His design put the wings, tail, and rear-mounted propeller into a

trailer towed behind the car.

To keep the weight down, Taylor fashioned the car's outer panels out of

fiberglass, years before the Corvette startled the automotive world with its

composite skin. And, because the rear wheels were used for landing, the Aerocar

employed what was then an automotive oddity: front wheel drive.The toughest

engineering challenge proved to be dampening the power pulses, or torsional

resonance, in the 10-foot-long drive shaft connecting the Aerocar's Lycoming

engine to its pusher propeller. After months of investigating vibration dampers,

Taylor read about a littleknown French dry fluid coupling called a Flexidyne. In

this clutch, tiny steel shot was packed into a nearly solid mass that absorbed

the engine's power pulses.

Taylor's Aerocar Incorporated turned out a prototype and four more examples

of the design known as Aerocar 1. In 1961, Portland, Oregon radio station KISN

bought one for traffic reporting. That was also the year Taylor first glimpsed a

bit of financial blue sky. He'd struck a deal with Ling-Temco-Vought, a

Dallas-based company. They'd build 1,000 Aerocars at a projected cost of about

$8,500 apiece, provided he could round up 500 firm orders. In two weeks he

collected 278 deposits of $1,000 each and forwarded the money. But without

another 222 orders, the deal fizzled.

Nine years later, Taylor's hopes rose again when Ford Motor Company took

an interest in the Aerocar 111. (the Aerocar 11 was a four-passenger flight-only

fuselage.) The Model III had fully retractable wheels, which cut drag and

boosted cruise speed 10 percent to nearly 120 mph. Lee Iacocca sent Donald

Petersen, a vice president of product planning and research (and later the

company's chairman), and Dick Place, a Ford executive with a pilots license, to

meet with Taylor in Longview.

Place's logbook dates his Aerocar flight to August 1970. He recalls being

sufficiently impressed with both the flight and highway performance to suggest

that Ford "at least take the next step or two investigating the possibilities."

But in the face of the oil crisis and increased importation of Japanese cars,

the company's interest cooled. And Place speculates that the career-minded

Petersen probably didn't want to be "weighed down with advocacy of what most

people would think of as a harebrained device."

Taylor made headlines with his Aerocars, but no money. In his basement was a

huge library of videotapes, most of them made from Super-8 footage. "Look at it

go, boy," he would say. "Now watch how smooth it lands. "'Here's Taylor, wearing

a fedora, standing on the old sod runway. He hears himself pounce on an

interviewer's question: "If it weren't for us nuts, you'd still be reading from

candlelight and wearing button shoes.... The flying automobile is the future. It

The marriage of automobile and airplane began early in the history of both

vehicles. In 1917, just 14 years after the Wrights first flew and nine years

after Henry Ford introduced the Model T, visitors to the Pan-American Aeronautic

Exposition in New York City gaped at a hybrid called the Autoplane. Built by the

Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company, the Autoplane was a three-seat car design

(in front sat a pilot/chauffeur, hence the nickname Flying Limousine) topped

with triplane wings spanning 40 feet. It flew, but never well enough to muster

serious interest.

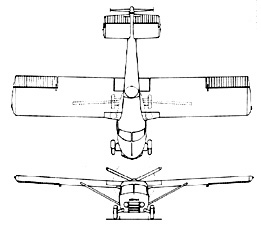

AEROCAR

PERFORMANCE

Top Speed ........Over 110

MPH

Cruising Speed ....Over 100 MPH

Rate of Climb (I st Min @ full

load) ...Over 550 FPM

Service Ceiling @ full load ...Over 12,000 Ft,

Cruise Range

.....Over 300 Miles

Landing Speed .... 50 MPH

Landing Run (with normal braking) ...300 Ft.

Take-off Run .....

650 Ft.

Distance to Clear 50 ft. Obstacle .....1225 Ft.

Designed

Road Speed (Engine red line)...67 MPH

Road Range .....Over 400

Miles

Fuel Consumption (Cruising)......8 GPH

Road Fuel ConsumptTon

......18 MPG

Time to Change from Plane to Car ......Five Min.

In 1937 airplane designer Waldo Waterman rekindled interest in a flying car

with his Arrowbile, a refinement of an earlier attempt he'd called the

Arrowplane. Its three-wheel design sufficed for short drives to the airport; it

fared worse on the open road. Airborne, it was said to be nearly stall-proof and

impossible to spin.

The 1940s was the golden age of the flying automobile. The post-World War

II boom in private aviation gave birth not only to Molt Taylor's Aerocar but to

Robert Fulton's Airphibian in 1946 and the ConVairCar the following year.

Fulton's craft flew well enough to be certified by the Civil Aeronautics

Administration, and, with its propeller detached and flight unit removed, drove

well enough to negotiate city traffic. The ConVairCar concept added a new twist:

It topped a two-door sedan with a flight unit containing its own powerplant,

which car owners would rent at the airport. Its creators talked of cars priced

at $1,500 based on production runs of 160,000, but talk ended after the

ConVair-Car crashed on its third flight, out of fuel because its pilot had

reportedly eyed the auto fuel gauge instead of the aero gauge.

In the 1950s and'60s, Leland Bryan produced a series of highway-certified

folding-wing Roadables that used their pusher propellers for both air and road

power. Bryan died in the crash of his Roadable III in 1974. And in 1973, Henry

Smolinski, mimicking the ConVaii-Car rental unit concept, fastened the wings,

tail, and aft engine of a Cessna Skymaster to a Ford Pinto. The wing struts

collapsed on its first test flight, killing Smolinski and the pilot.

"To

me, its simply a question of time," says Branko, Sarh, a senior engineer at

McDonnell Douglas Aerospace in Long Beach, California. As a teenager in Germany,

Sarh was sketching flying car designs long before he ever heard of Molt Taylor.

He studied aircraft and automotive design in college, and at the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology in the early 1980s he began concentrating on composites

and automation, two key elements of his futuristic Advanced Flying

Automobile.

"If someone today says flying cars, everyone looks backward, into history,"

Sarh says. "Oh, they were produced already: Curtiss and Taylor and ConVair. All

these were excellent pioneering efforts. It was perfect to prove that a car can

fly, but that's all they proved." Sarh feels the time is ripe-thanks in part to

recent advances in lightweight composites and computer modelling techniques-for a

major leap, well beyond some warmed-over newsreel version, to an entirely new

flying car concept. His design, unlike most, puts the car before the airplane.

His reasoning: "People will mainly see this vehicle on the ground. This must be

a perfect car, first of all. The styling must be superb."

A similar lack of funding has stalled Ken Wernicke's Aircar, which last year

made the covers of both Popular Mechanics and a special issue of Discover.

Known as "Mr. Tiltrotor" at Bell Helicopter Textron, where he worked for

35 years, Wernicke was lead engineer on the XV-15 and director of the V-22

Osprey Tiltrotor. He took early retirement in 1990.and formed Sky Technology,

based in Hurst, Texas. He put its mission right on the company's letterhead:

Specializing in Revolutionary Aircraft. Case in point: the Aircar.

The concept of vehicles that could transform themselves from automobiles to

airplanes dates back to the earliest days that the two both existed. The

ubiquitous Glenn Curtiss produced a design for a three-seat flying car in time

for the Pan-American Aeronautic Exposition in New York in February 1917. It

flew, but poorly, and was scrapped. Subsequent literature ranges from stories of

backyard tinkerers to the fantasies that Ian Fleming imagined to get James Bond

out of tight situations. There was, of course, Waldo Waterman's

Studebaker-engined Arrowbile in 1937 and the Pitcairn PA-36 Whirlwing of 1939, a

mongrel autogiro that was actually designed by Juan de la Cierva.

Despite the alluring appeal of these vehicles, they are an instance where

theory and practicality never crossed paths. In the optimistic days after World

War II, however, anything seemed possible. Technology promised backyard

heliports and suggested that ownership of private airplanes would be as common

in the late 1940s its automobile ownership had been in the 1930s. It was only

reasonable, therefore, to predict a solid market for flying cars. Dozens were

proposed, and some were actually built and flight tested.

The Boggs Airmaster, designed by HD Boggs and marketed by Buzz

Hershfield, included a 16 foot car with a 35 foot wingspan powered by a 145 hp

engine, but it was never built, The Spratt Controllable Wing car, which appeared

in late 1945, featured a pusher prop and a flexible wing mounted on a swivel

behind the two-passenger cab. George Spratt later teamed up with William B Stout

(who had merged his Stout Aircraft Company into Consolidated Vultee), in a vain

effort to market the vehicle under the tradename Skycar.

The unique Hervey Travelplane, which also appeared in 1947, had a

single dural tail boom which passed through the pusher propeller shaft to

support the tail surfaces. The propeller was, in turn, driven by a 200 hp Ranger

engine that promised four hours of air time at 125 mph. Designed by George

Hervey of Roscoe, California, the Travelplane had a 16 foot automobile and a 36

foot wingspan. Conversion from airplane to automobile took six minutes when

Hervey demonstrated it.. although customers might spend a bit more time -an hour

or so- until they learned the ropes. The wings could then be stored in a

'convenient' trailer unit. There was no provision, however, for airlifting the

trailer.

The Whitaker-Zuck Planemobile was 19 feet long, with 32.5 feet of

folding wings. Built in 1947, it solved the problem of what to do with the wings

by simply folding them across its back, to be carried like a hermit crab carries

his shell. The Taylor Aerocar, built by Molton Tavlor of Longview. Washington in

1949, was a V-talled bird whose wings folded neatly into a self contained

trailer for easy towing.

Robert E Fulton's FA-3 Airphibian

was not amphibious but rather

'airphibious,' a two-place airplane whose forward fuselage could simply 'drive

away' from the rest of the airplane upon landing. It first flew on 7 November

1946, but never progressed beyond the prototype stage.

Of all the projects that developed in those idealistic days after the war,

there were none that came so close to getting into the commercial mainstream

than the creations of Theodore P 'Ted' Hall, an engineer at Consolidated Vultee

Aircraft in San Diego, who quit his job at the end of the war to pursue his

dream. Joined by Tommy Thompson, a friend and former Consolidated colleague,

Hall began work on his dream in 1945. Forming the light-gauge aluminum sheets

with a rubber hammer around a tube steel framework, Hall, Thompson and their

small crew set about to hand make the first prototype. They picked a 90 hp

Franklin to power the airplane part, and lifted a four-cylinder 26.5 hp engine

from an old Crosley auto for the car half. In fact their compact little vehicle,

whose interior was about the same size as a Volkswagen 'Beetle.' looked a bit

like a Crosley, except for its being, mounted on a three-wheel chassis.

Having completed the Hall Flying Car, the southern California

entrepreneurs successfully test flew it, and wound up being the subject of a

feature in a 1946 issue of Popular Science magazine. In the meantime, Hall and

Thompson had been beating the bushes for someone who would underwrite the

production of their brainchild. A proposed deal with Portable Products

Corporation in Garland, Texas had gone by the wayside, when Hall struck a deal

with his former employer.

Suffering a severe sag in airplane orders because of the end of the war.

Consolidated Vultee Aircraft (now known as Convair) was keen for new business,

and the conventional wisdom was that the United States was on the threshold of

an unprecedented boom in general aviation. Every major airplane manufacturer was

anxious to cash in on the 'airplane in every garage' future, and Convair was no

different. so they bought out Ted Hall and moved the project into their main

plant at Lindbergh Field near San Diego. Convair predicted a huge market for

Hall's vehicle among travelling salesmen. They even went so far as to buy the

Stinson Aircraft Company-a well-known general aviation manufacturer-as a conduit

for producing and marketing it. They also had acquired Stout Aircraft, which

was, as noted above. also involved in a similar project.

Who wouldn't stop

and look over these 1950s ads for the Aerocar !

A second version of the Flying Car was developed, which differed from the

original by its having a conventional fourwheel layout on the car, and a single,

rather than double, rudder arrangement. This craft, now designated as the

Convair Model 118 ConvAirCar. was ready to fly in July 1946. Hall and a Convair

test pilot took it up to 2006 feet, made a couple of turns over ihe field and

touched down. Convair management was delighted- They predicted minimum sales of

160,000 units with a retail price tag of $1500- The wings would be extra.. but

you could pick those up at any airport on a one-way rental basis.

Ultimately, however, only two Model 118s were built, with the second being

completed in 1947. This ConvAir-Car incorporated the fibreglass body envisioned

for the production models and had a 190 hp Pratt & Whitney radial engine

that could propel the vehicle at 125 mph in the air.

Early in November 1947 misfortune struck, The second ConvAirCar took off on a

routine flight during which the pilot misjudged his fuel. They ran out of gas

and were forced to make an emergency landing on a dirt road. The pilot walked

away, but the wings sheared off and the fibreglass body was beyond repair.

In a decision based on the publicity surrounding the crash and the huge

number of cheap former-military airplanes flooding the market, Convair abandoned

the programme and sold the hardware back to Ted Hall. He is reported to have

retired to New York, although the prototype ConvAirCars are reported to be in a

warehouse in El Cajon. California.

The end of the ConvAirCar was really the end of practical hope for flying

cars in the United States. If a company like Convair, with all its resources

couldn't do it, then it probably wasn't going to be economically viable. In

retrospect. there is a certain allure held bv flying cars on a warm summer

evening in Southern California, but when one pictures 160,000-or even 160-flying

cars airborne during a January storm over Chicago, New York or London, the idea

is a lot less practical. In the very areas where the people live who would make

use of flying cars, the airspace is much loo crowded for such flimsy craft flown

by pilots with marginal experience.

|