A written

list of the qualities you

would like to see in your aircraft is an absolute necessity. It might contain

such requirements as:

Ease of construction

Ease of construction

Low landing/take off speed

Low landing/take off speed

High rate of climb

High rate of climb

Good cruise speed

Good cruise speed

High ceiling

High ceiling

Comfortable seating space

Comfortable seating space

Outstanding visibility

Outstanding visibility

Acceptable noise level

Acceptable noise level

Easy ground handling

Easy ground handling

Good visibility during taxiing

Good visibility during taxiing

Good handling in the air

Good handling in the air

Large panel to show off with full IFR

Large panel to show off with full IFR

Excellent low speed controllability

Excellent low speed controllability

And the list could go on and on. There may be some very special

things you need in order to make your aircraft truly useful for your individual

life style, such as:

300 ft. roll take off and landing (because your private

strip is only 600 ft. long).

300 ft. roll take off and landing (because your private

strip is only 600 ft. long).

40 lbs. baggage capacity (because your better half likes her

creature comforts -but remember, you'll have to

40 lbs. baggage capacity (because your better half likes her

creature comforts -but remember, you'll have to

carry it to the motel!)

carry it to the motel!)

260 lb. pilot (because you do not like diets)

260 lb. pilot (because you do not like diets)

good high altitude performance (because you live at 8,000

ft.)

good high altitude performance (because you live at 8,000

ft.)

adaptability on wheels or floats (because you live in town

but your cottage is on the lake)

adaptability on wheels or floats (because you live in town

but your cottage is on the lake)

removable or folding wings (because hangars are too

expensive).

removable or folding wings (because hangars are too

expensive).

After the first general list of desired qualities, and the

second more individually specific list, a third more practical list should be

developed, including such basic questions as:

Can I build it?

Can I build it?

What's the total cost?

What's the total cost?

Can I design it (or is the designer reputable so that I can

trust his design reliability)?

Can I design it (or is the designer reputable so that I can

trust his design reliability)?

Will it have low maintenance costs?

Will it have low maintenance costs?

Will it be easy to maintain?

Will it be easy to maintain?

Now that you've made these lists, make a couple of copies and

hang one on your workbench, one on your desk, etc. to look at and think about

for a few weeks. Refer to them from time to time, adding as many things as you

like until you feel you've got all the appropriate variables covered.

With all this information in mind, you have the framework to

start looking at aircraft. As a designer of many original aircraft, I am not

talking here about a "reproduction" aircraft, but a brand new design in which

every part will be checked for adequacy according to present day,

state-of-the-art technology. In other words, we're going to start from scratch

and not consider a Cub wing on a Citabria fuselage with a Cherokee tail and a

Cessna gear. Rather we're going to think about a new design where a 12 hp engine

can take off with four people in 300 ft, at 3,000 fpm, cruise just below the

speed of sound for 8 hours, come in a kit that can be built in 50 hours for less

than $3,000, with a designer who is willing to spend 120% of his time improving

his design to the builders suggestions!!

All jokes aside, before I put someone into cardiac arrest

thinking such an aircraft could exist, we have to stay realistic. Our

machine will have to be built with known raw materials, using well proven

techniques, and the design will be subject to gravity (earth attraction) drag

(wasted energy), and powerplant efficiency just like any other. So, of

necessity, we must start out with certain basic limitations, but we won't let

that discourage us because there are many proven, good designs available. We

certainly can design one ourselves or find an already existing design that meets

our needs.

Now, we'll go back to our lists and this time we'll strike out

the unreasonable items. This is simply a matter of common sense. We all

have common sense - it just gets a little bit damaged sometimes during our

formal education, but if we are to have any success in life, we have to listen

to it very carefully. If we dream the impossible we will become a dreamer unless

we are geniuses. But experience tells us that geniuses are the exceptions, so

the majority of us has to live with common sense. Reality puts us back on track

when we listen too much to our dreams.

The next step after our lists have been made reasonable by

common sense is to rearrange them. This time we'll combine all our variables

onto one list and rearrange them in a decreasing order of importance.

Now, our list may look like this:

Low landing speed

Low landing speed

Outstanding visibility

Outstanding visibility

Low cost

Low cost

Comfortable seating for two

Comfortable seating for two

400 lbs. (pilots and passenger and baggage)

400 lbs. (pilots and passenger and baggage)

or this:

Low cost

Low cost

Design confidence

Design confidence

Reasonable cruise speed

Reasonable cruise speed

Good handling (air and ground)

Good handling (air and ground)

Removable wings

Removable wings

Our list may still contain some

incompatibilities, such as low

cost and high cruise speed, or sexy looking design and low maintenance etc., so

now is the time to eliminate the incompatibilities or change each one slightly

to bring them closer together. Using the previous example, we could have

acceptable cost (say $30,000) and cruise at 150 mph or have a good looking

airplane with acceptable maintenance (less than 1 hour to remove all

fairings).

We have to be very careful when interpreting adjectives (what

is good looking to me may be ugly to you, what is acceptable to him may be

unacceptable to her!). In order to avoid misunderstandings on this subject, our

civilization has unsuccessfully tried to quantify everything - and I say

unsuccessfully because quantifying will stay just that as long as we deal with

human beings and not strictly with machines. (I classify computers as machines,

too, by the way)

We all know how the same statistics can be used to justify

white or black, blue or red depending on the speakers beliefs and skill of

convincing others. But we are not in politics, not even at a sales or hangar

flying session. We are simply trying honestly to design a good new aircraft. But

we need figures so we have to write them down and as we work with gravity

(weight), drag (pounds) and other physical qualities, we add onto our lists

whatever we can quantify, being aware that some items (numbers) may have to be

left blank.

Our list may look like this:

Stall below 45

Stall below 45

Visibility 360 degrees

Visibility 360 degrees

Airframe cost below $14,000

Airframe cost below $14,000

Comfort ( )

Comfort ( )

Must carry two (400 lbs)

Must carry two (400 lbs)

or this:

Total cost below $30,000

Total cost below $30,000

Reliability ( )

Reliability ( )

Cruise speed 120 mph

Cruise speed 120 mph

Handling ( )

Handling ( )

Removable wing (7-1/2 ft. max)

Removable wing (7-1/2 ft. max)

Now, we have to start compromising. It is this accepted

compromise which will make for a successful long-term choice. For example,

one has to compromise between 360 degrees unobstructed visibility and a high

wing: either you stay with a high wing (which needs hefty uprights) and reduce

the visibility requirements, or you stay with 360 degree visibility and have to

install a bubble canopy on a low wing aircraft.

The same applies for low stall speed, high cruise speed and low

cost (here we have three variables). High cruise speed means large wing, high

lift airfoil, low powerplant and fuel weight. Low cost means single wing (no

retractable high lift devices) a small wing and low horsepower.

So, one goes down the list again and again compromising and

keeping in mind that the items were listed in a decreasing order of importance.

After making more adjustments to reduce any incongruities, the next thing we'll

need to do is work with some calculations.

Weight:

Statistics show that the

empty weight of most aircraft is close to 60 percent of the load carried

(passengers and fuel). As you have a good idea of the engine, add the fuel

required for the desired endurance (as a rule of thumb, if the engine is rated

at 100 hp, you'll burn 6 U.S. gallons per hour at 75 percent cruise and 1 U.S.

gallon weighs 6.0 lbs. For example, with 120 hp and 3 hours range, you need 130

lbs. of fuel, so the gross weight (W) in lbs. equals 1.6 (occupants plus baggage

plus fuel).

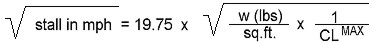

Wing area:

You know the maximum

lift co-efficient (CLMAX) of the chosen airfoil (if you have no better idea, use

1.4 no flaps, 2.2 for the portion with flaps, and 3.0 for flaps and leading edge

slots) and can calculate the wing area (S) knowing the desired stall

speed:

Your top speed will be close to

(for a very clean aircraft you may replace 190 by 21

0)

Your cruise speed is some 90 to 95 percent of the top

speed.

You will have an idea of the climb performance by

calculating W/S x W/ BHP = P

Where W = gross weight (lbs.)

S = wing area (sq.

ft.)

BHP

= Rated Brake

Horsepower of engine

The "statistical" diagram below gives you very good take off

and climb performance if your aircraft is below the curve.

These calculations are the basis for making some design

decisions. Combining the results of these calculations with the variables on our

list will begin to make our design choices fairly obvious, thus we are on our

way to beginning the actual design, or choosing the design, that we are going to

build.