Over the years I have seen some pretty homebuilts and some even nicer

production planes, but if one should look closer and peek underneath the

control panel, the truth is normally revealed regarding the competency of

the builder or service organisation maintaining the production plane.

The electrical wiring on most of these planes leaves much to be desired,

whether homebuilt or other. As a homebuilder involved in quite a number of

projects over the past 15 years, I have picked up the skills to assist

most of the homebuilding fraternity in SA with advice regarding how to do

the electrics, avionics and intercom systems on their planes.

One would expect aircraft wiring to be

complex, well, let me inform you that the technology used in aircraft

mostly dates back to the 50's and 60's, (and even before that!!) and that

only the very wealthy can now days afford the state of the art technology

for homebuilts and they are most probably not into homebuilding anyway.

So, that leaves you with the only choice and that is to do all the wiring

and radio/avionics installations yourself.

planning your wiring

Before

one rushes off to the local hardware shop, buy some wire, a couple of

fuses etc and attempt to start wiring you plane, there is a lot of

planning that you have to do.

Firstly, you need to know what

electrical equipment you will be installing in your aircraft and you will

have to sit down and plan your wiring diagram and the relevant

component/parts ratings. There are plenty of good books and articles in

various aircraft magazines on how to do this.

My intention is not to repeat all that

good work in this article, but to assist that you do not make unnecessary

costly or "ugly" mistakes. One of the ugliest things that you can do to

your airplane panel is not allowing enough room for spare circuit breakers

and switches and you then have to add afterwards onto a secondary panel or

even worse scatter the breakers and switches all over the show. You will

also have to make a decision on whether you will have one electrical bus

or two. I now days recommend that you have a main electrical bus and a

radio/avionics bus. The reason for this being that you now have a choice

to install a "radio" master switch in between the two busses. This feature

is very handy during start up and shut down, as one switch "kills" all

avionics and you don't have to change volume settings etc.

Another

thing that you will have to decide during your planning session is where

on your control panel you will be housing the switches and circuit

breakers, as well as your indication lights, voltmeter, and ampmeter. Yes,

I recommend both a voltmeter and ampmeter. These instruments are fairly

cheap and can save you a lot of grief once you realise their potential.

Another

must is that you retain control over your alternator field, so you will

need a switch to switch off your alternator field. The voltmeter will tell

you whether your voltage regulator is working properly (13.8 V to 14.2 V)

and instead of blowing your expensive radios if the voltage regulator goes

faulty (usually results in an over voltage), you can switch off the

alternator field and revert to battery power. ( Seeing that it is not that

easy to switch off your engine in order to save the radios when you are

flying!)

designing your control

panel

Now gentlemen

(and ladies), most of the aircraft that I have worked on so far are fairly

cramped underneath their control panels and I am over 6 ft tall. If you

fall into that category as well, do yourself a favour and design your

control panel with drop down panels for everything - What do you mean, you

will say? What I am hinting at, is that you design your panel with a back

skeleton base and loose panels that will fasten from the front by means of

screws and rivnuts (if you don't know what rivnuts are let me know and I

will do an article on them as well) So, have a panel that you can sit

comfortably in your pilots seat and work on everything, by loosening the

various panels and secondary panels and dropping those into your lap!..

yes, you have guessed right, you have to leave enough slack in the wiring

to do just that . (Another advantage is thus that you don't wake up with a

severe back ache on the Sunday morning)

My

recommendation be that you have at least the following individual dropdown

panels; flight instruments, electrical switches and magneto switch, engine

instruments, radio stack, circuit breakers (heavy current stuff like

landing lights, navigation etc), separately from that of the avionics

circuit breakers. Once something goes wrong (and it does - believe me) you

can quickly remove the culprit panel and fix it. (presumably not in

flight!!!).

What you have probably realised from the

above is that you can not really do the planning of the wiring on your

aircraft in isolation and that there are many factors like panel design

that you also have to consider right from the onset. Please do yourself a

favour and get a big enough piece of cardboard and draw your control

panel, instruments, switches, circuit breakers, pull knobs etc actual

size. You will in that way find whether you can in fact reach a particular

switch for instance, in flight without ducking you head underneath the

panel (and entering a spin, should you not be careful.)

To

properly plan your layout you will also need the actual sizes of all the

components that you want to accommodate on the panel. Now is also a good

time to start acquiring all these components. Make sure that you find

circuit breakers or fuses with the correct ampere ratings. If you can't

find the correct aircraft quality components you may use ordinary

commercial stuff, but please test these to destruction and if the rating

on a switch says 10 A, limit what you want to break to only 50% of that. I

have found rocker switches which are commercially available for an

electrical stove, to be quite robust and that the contact gap once open,

is quite wide, which is good for spark quenching purposes.

In the photographs you will see the

rocker switches that I have used on the Piper Tripacer that I am busy

restoring. I have also made sure that there will be no confusion whether a

switch is switched on or off.

As

pilots I know you are not colour blind, so you should be able to spot the

switches which are turned on. Please note that the current ratings given

for these switches will be for AC and that it is more difficult to break

DC, hence you have to test samples of the component types that you intend

using to destruction.

If you find that you want all your

switches to look similar, but the landing light for instance consumes more

amperes than the switch can withstand, don't despair, just employ a slave

relay of the correct contact rating for that circuit.

summary

Well, Now you should have the following

wrapped up; Your wiring diagram, with bus choices and circuit ratings

showing all the devices (loads) you will be installing as well as the

spare slots. Your panel layout, ie. Switch positions and type, circuit

breaker panels, volt and amp meter positions and a general full scale

panel drawing.

All your switches, circuit breakers,

volt and amp meter all tested and physically in hand.

general

Now

that you have your planning complete, it is time to seriously get all the

components and tools together. As promised, here is the second article on

wiring. It will really pay to invest a little in the correct tools and

methods on wiring. The tools that you require to do wiring are not very

expensive and I therefore recommend that you purchase these.

Either way you will have to ensure that,

firstly you perform a proper job and secondly that when you have to add to

your wiring you do so in a consistent manner. Let's discuss the tools

first.

tools required to do wiring

I

have a long time ago decided that I will buy a plastic toolbox for wiring

purposes only and this has worked well over the years in the sense that it

has "kept everything together". The advantages of this box being that I

don't have to hunt around for my stuff should I want to perform a wiring

job. In the attached photographs you will get an idea of what I have done

and how I have grouped everything. So, What do you have inside this

toolbox one may ask?

Well, it is a combination of tools and

essential consumable wiring spares. Inside I have, two soldering irons,

big and small, solder, wire insulation strippers, long nose pliers, side

cutter, soldering flux, heat shrink insulation of various colours, lengths

and sizes, wiring letters, spare switches, spare relays, cable straps of

various sizes and colours, a copper bus bar or two!!! etc. You will also

find it handy to have a heat gun to shrink the heat shrink insulation.

Another

"toolbox" that I have is also displayed in the attached photographs and

that is the one with all the compartments having all my various lugs.

(some people call them bits). To do wiring you will also need a

multi-meter or continuity tester to "ring out" the correct circuit. Which

Wire must I choose? A number of homebuilders are quite unsure which type

of wire to use. Make sure that your wire is rated for the ampere that you

want to transport to your various loads.

And, yes, if you can find aircraft wire

please use that and never use PVC covered wiring as used in most cars.

Proper aircraft wire is very tough and will not easily chafe and nor does

it burn well, where PVC gives of a nasty stench. (and smoke). If you can

not find aircraft wiring anywhere, go for silicone insulated wire. One

word of caution here, silicone insulation works well and does not burn,

but it is very soft and care must be taken that it does not chafe

anywhere. It must also be "suspended" more than aircraft type wire due to

the softness, but then on the other hand cable straps are quite cheap to

hold the wires in a loom.

busbar construction

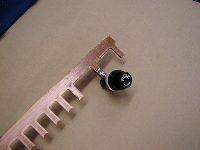

A very nifty

way of constructing a busbar is to use a 'fingered' copper bar that is

obtainable from your local electrical shop, as used on household

switchboards. See the attached photographs for a picture of how I have

used this in conjunction with a fuse holder.

I have removed every second "tooth" on

the copper bar and that allows a nice spacing of approximately 25 mm

between fuses. Your secondary positive wire from the battery via the

master relay and ampmeter, will terminate on this bus to supply all the

loads. The positive from the alternator will also terminate here.

These

must be the only non-load wires connected to the bus ie. those from the

two power sources, namely, alternator and battery. Please connect the

alternator to this bus through a 60 amp slow blow in line fuse or suitable

DC circuit breaker. The fuse holder(s) on the load side of the positive

busbar might be substituted for a circuit breaker(s). It is best to employ

both a positive busbar and a negative. (More about this in the final

article on earthing.)

to solder or crimp the terminations?

Bad crimp connections can result in a

forced landing as recently happened to a very dear friend of mine. (who

will remain nameless for the here and now, but he did make it back to the

runway - well just!.)

To find the intermittent connection is a

mammoth task and you can spend days underneath your control panel where I

am sure you would rather fly. I have developed my own method/technique to

ensure that I have performed a good crimp and this is simply to make sure

that I have not accidentally cut off one of the wiring strands, and once I

have made the crimp I pull hard on the lug and the wire to see if they

will part. I have found that at least one in ten crimped joints will

separate and then you have to do it over again (new lug- don't use old

one), but loosing those few cents that the termination is worth, is much

hurting less than a forced landing. I still prefer to solder the lugs on.

As

you will understand the weakest point will then be where the insulation

stops and the lug body begins. To strengthen this I use a good quality

heat shrink to cover the wire and the body of the lug. See the attached

photographs to see what a good soldered termination looks like, with and

without the heat shrink insulation. Where you will be drawing heavy

current it is always best to solder, as this will prevent corrosion taking

place "inside" the crimp.

Please

also ensure that you have the correct size hole in the lug for the screw

termination on the circuit breaker or switch and never use lugs with an

open split end or of the 'push over' type. If you have to use these,

(voltage regulators are 'fond' of having this type of termination) make

sure that the wiring loom does not pull onto the wiring pin termination,

thus causing it to "pull off" and end up as a disconnection.

wiring loom separations and stringing / suspension

When I recently wired an aircraft for a

friend, I have made use of the technique where I used different looms for

different purposes, being separated and routed, where possible, along

different routes or at right angles to avoid radio interference.

So, you will say - What on earth is he

telling us. Well, make sure that you have at least the following separate

wiring looms. One for the master switch circuit, starter circuits, landing

light, nav lights and other heavy loads like under carriage or flaps,

another for the intermediate current circuits and electrical supply to the

avionics and then a totally separate loom for the intercom and

microphones/headsets. (I will discuss this in more detail in the last and

final article).

To enable me to "find my way around"

under the panel, I use various coloured cable straps for the various

looms, but this you may choose to your liking. (For the majority

production planes that I have seen, all marching on in years, you will

find all wires bundled together in a rather untidy model..) Never run your

wiring diagonally across the shortest route from one point to another, but

always parallel to the bottom of your panel or at right angles.

Make sure that you manufacture little

pillars or supports to suspend the wire looms from. I have found that RSGU

clamps work best when you want to achieve this. Also make sure that you

have enough slack in the wires that you do not get "guitar string "

vibration effects.

You can call me a liar, but I have seen

a wire like this on a plane once a couple of years ago and when you

displace this wire slightly to the side, it will make a "boing- boing"

sound. Another advantage of enough slack will be that if you want to

re-route a particular wire or connect it to another circuit, the wire will

be long enough (hopefully) and you don't have to cut all the cable straps

in the loom to get the offending wire out. Most people just give up and

splice the wire! Now, that is a dangerous practice if you don't do it

properly and needs to be avoided. Should you want to go that route, please

make sure that you use at least two layers of heat shrink isolation and

that the wire ends are twisted and soldered. However, please avoid this

technique.

summary

You now have all the tools together, you

have chosen the wire and the lug sizes, know how to perform crimps and

soldered terminations, and have planned your wiring looms and respective

routes. All that is now needed is a lot of care in performing the job.

So, you have opened the box that the

brand new intercom that you ordered at great expense from the States

arrived in, and the miniature connectors on the side looks like some

computer part and the wiring diagram is very "full". Hmmmmm, well, the

best thing to do here is read the instructions and once you have read

them, read it again. Then try and find somebody that has done this job

before and contract him/her?.

Anyway, let me explain a couple of

fundamental issues to watch out for during the installation of an

intercom.

terminations and

connections

The majority of recently designed

intercoms on the market make use of small light integrated electronic

circuits and the objective is to make it as small and light as possible.

It is for an aircraft anyway and every ounce helps, not so…. Right?

This will however present you with one

problem and that is in fact to connect it to normal wiring of the

aircraft. These small multi plug push in type connectors do not allow for

multiple wires to be soldered on, rather a multi core cable, and you thus

have to make use of an intermediate connector or circuit board. I have

found that the easiest way of doing this is to design a circuit board

(like in the back of a radio) and have the copper tracks etched, drill the

miniature holes, make your connections and mount other electrical

components like miniature relays etc. I have successfully used miniature

relays to cut out all the other mikes to the intercom during a pilot

transmission. This solely depends on the type of intercom that you have

purchased.

With the fancy voice operated intercoms,

this is not necessary or when the PPT button is activated, the intercom

disables the other mics. If you don't know which connectors will be the

best to wire your intercom ask a radio technician.

use of screen cable

To

avoid any interference you must use screen cable on all the audio

circuits, even to the speakers of the headset. (Screen Cable is also known

as Microphone cable to some people - impedance of 75 ohms - and has a

centre core and a woven wire shield around that that acts as an electrical

shield- please see the photograph at left).

Aircraft screen cable was previously

produced with the wire shield not insulated and my recommendation will be

not to use this type, as it could lead to earthing loops etc. Even the wire to the PPT button must be a screen cable.

A good quality screen cable (woven) is

obtainable from most electronic shops and some are available with a

silicone outer shield. That is the type you must buy. (Obviously it will

also be the most expensive, but please invest in it as it is worth your

while)

single earth point

(maybe!)

Create a radio/ intercom negative bus

that is insulated form the frame of the aircraft. Yes, you have read

correctly, make sure that it is insulated and then connect this bus by

means of one heavier cable to the most suitable "earth" on the aircraft.

The negative terminal on the battery works best.

Now, where the "little" wiring diagram

that you received with your intercom shows earth points, connect all these

to this radio/intercom negative, but be careful to read the instructions

first. Some intercoms would not allow this and needs an intermediate

earth. This means that all the screen cable screens for the mics and

headset speakers get connected to a single point on the little box and

then another wire runs from the little box to your radio earth which then

connects to the battery.

What the engineers have thus done is to

put a low pass filter in the negative line to filter high frequencies from

the negative circuit. This practice is employed to prevent earth loops or

paths which "stray induced currents" can follow. The effect of these

currents would be excess noise or hum on the intercom. Another item to

watch out for is to make sure that the jack sockets (base) for the

headsets are mounted on an isolator (like Perspex) and not to the metal

frame of your plane. The negative screen is then earthed at the

intermediate point on the intercom box and not via the socket to the

aircraft frame as this will create a possible earth loop.

Following the practice described above

will get you out of trouble……well, most of the time. In Article two I have

mentioned that you must create separate wiring looms, and the intercom

cables are ideal for doing this. Keep them away from the heavy current

circuits and route them separately.

your radio needs an antenna

Your radio needs an antenna to receive

and transmit and it must be properly wired to get the best results. Hey,

you have'nt to tell me that, you will say. Well, here are a few tips.

You have a choice of antennas. You get

the quarter wave dipole one, like on most cars, aircraft, and hand held

radios, then you get a VOR type antenna, like on the tail fin of a number

of expensive aircraft (normally a V shaped wire contraption) You may use

any of these for VHF transmissions. Whichever one you have, it must still

be wired correctly, and here is how. Yet again you will need screen cable,

but with an impedance of 50 ohms with trade name RG58. (No, television

cable would not do as it has an impedance of 75 ohms…..I saw a homebuilt

the other day where the guy has in fact used television cable……..)

This cable connects to the radio by

means of a BNC connector and let me warn you, to connect the cable and the

BNC connector together takes some practice and figuring out, patience and

a steady soldering hand. Those of you who have done this before will know

what I mean. Once you have soldered it on, make sure that you don't have a

short at this connector from the centre core wire to the shield, as a

short at this point will certainly blow the class C stage of your radio

during a transmit.

When you plan the position of your VHF

antenna on the aircraft, make sure that you position it as close to the

radio as possible, as a long cable will attenuate the signal. So, to have

your antenna on the rudder, might be very fancy looking, but it might not

work all that well in practice due to the long cable. Generally, the

shorter the better.

On composite home builts you will need a

metal ground plane at the base of the antenna, at least of 50 cm in

diameter, where you use a quarter wave dipole type antenna. Make sure that

under no circumstances the ground plane can short on the rigid bare metal

antenna. If the ground plane is not earthed to the negative bus, the

shield of your antenna cable must be connected to this ground plane. (Only

composite or wooden aircraft)

Should you have a metal aircraft, make

sure that the antenna cable shield is only earthed on the radio side at

the BNC connector. This is to avoid an earth loop via the antenna cable

shield. For a metal aircraft there is no need to provide a ground plane,

as the aluminium frame acts as a ground plane. For the VOR type antenna,

the centre core of the antenna cable is connected to the "one leg" of the

V of the antenna, and the shield to the other leg. The "negative" antenna

then acts as the reflector.

You can also "tune" your antenna to the

most used frequency by making it the "exact" length. EG, say you are using

a quarter wave dipole, the length of the antenna (above the ground plane)

at 124.8 Mhz will be 60 cm.