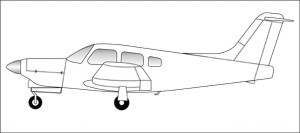

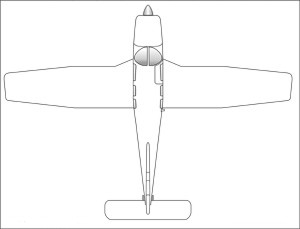

The Arrow,

since it’s really just a retractable

Cherokee (or Archer), is a logical step-up

airplane for pilots who now fly fixed-gear

Pipers. Everything will be familiar, from

gauge placement to handling and procedures.

And that, of course, was the basic marketing

model for all of the major manufacturers in

the 1960s and 1970s: train pilots in

two-seaters, graduate them to similar

four-place, fixed-gear models, then to

retractables from the same blood line.

History

The ubiquitous Piper PA-28 has been folded,

stapled and extruded into an almost

unbelievable number of variants over the

years, from the modest Cherokee 140 trainer

all the way through the T-tailed Turbo Arrow

IV — including the Warrior, Cherokee 180,

Archer, Cherokee 235, Dakota, Challenger,

Charger, Pathfinder, Cherokee 150,. Cherokee

160, Arrow, Arrow II, Arrow III... and a few

turbocharged models in there for good

measure. The PA-32 series also shares the

same basic design, and, by extension, the

Seneca. The PA-28 airframe, too, was made

into a twin, in the form of the Seminole.

The original

PA-28 owes its existence to John Thorpe, who

designed an all-metal homebuilt that, after

some modifications, became the first

Cherokee. Introduced in 1962 as the Cherokee

150 and 160, the PA-28 gave Piper a badly

needed shot in the arm in the low-end

market. Cessna had a runaway success on its

hands with the 172, and Piper’s competition

— the Tri-Pacer — was downright dowdy by

comparison. In the retractable market, Piper

did have the sleek and handsome Comanche to

sell, however.

The Cherokee

did well, and was soon joined by the 180 and

235, giving Piper a strong lineup of

fixed-gear singles suitable for a variety of

missions. Since all Cherokees shared the

same basic airframe, the company was also

able to realize some manufacturing

economies.

By the

mid-1960s, Piper began considering the PA-28

as a candidate for penetration into the

light four-place retractable market. At the

time, Mooney effectively owned that niche.

Beech’s least expensive retractable was the

Debonair, which cost a third again as much

as a Mooney, and Cessna had no comparable

airplane at all.

Piper outfitted

the Cherokee 180 with folding legs, and in

1967 unveiled the first Arrow. It was every

bit a Cherokee, from the fat, constant-chord

Hershey Bar wing to the stabilator. The base

price was $16,900, some $1,350 less than the

Mooney M20C Mark 21 (according to the

Aircraft Bluebook Price Digest, however, the

average equipped price of an Arrow as

delivered was actually about $2,000 more

than the Mooney). A Cherokee 180 from the

same year had a base price of a mere

$12,900.

The PA-28R-180

came with a constant-speed prop attached to

a Lycoming IO-360-B1E engine. The new

retractable gear was electromechanical

(compared to Mooney’s distinctive manual

arrangement), and had a unique feature: an

auto-extension mechanism that would lower

the gear if the airplane slowed below a

certain airspeed. It was intended as a

safety feature, and Piper touted the Arrow

as the perfect airplane for pilots

transitioning to high-performance,

retractable-gear airplanes. Many pilots and

insurance underwriters loved the “foolproof”

gear system. Some insurers even assigned

lower rates to pilots without much

retractable time. It was hoped that the

automatic extension system would end

aviation’s most common, embarrassing and

preventable mishap—the gear-up landing.

The original

Arrow compared well with the Mooney in some

departments, such as roominess and cost.

However, it fell short in terms of speed...

but then, nearly all airplanes do. Cruise

was pegged at 141 knots, compared to 158 for

the Mooney. Still, the Arrow was

considerably faster than the carburetted,

fixed-gear, fixed-prop (but otherwise

identical) Cherokee 180.

After two years

and sales of almost 1100 airplanes, Piper

came out with a 200-HP version of the Arrow.

The extra $500 it cost gave pilots a

Lycoming IO-360-C1C engine, a few knots, and

a 100-pound boost in gross weight, though

that was eaten into by a 79-pound increase

in empty weight. The C1C engine was more

costly in other ways, too — it had a

1200-hour TBO, compared to 2000 for the 180.

That has since been remedied through the

retrofit of new exhaust valves, and it’s

unlikely that any of the 1200-hour mills are

left. The TBO for the 200 is now also 2000

hours.

The 200-HP

Arrow was sufficiently more popular than the

180 that the latter was dropped in 1971.

Starting with the 1972 model year, the

airplane was redesignated Arrow II. Its

fuselage was stretched five inches,

providing more rear-seat room; its wingspan

was increased 26 inches, and the stabilator

was lengthened in span. This allowed 50

pounds more gross weight, and the addition

of the long-awaited manual gear-extension

override. Thanks to larger bearing dowels,

the old 1200-hour TBO was boosted to 1400

hours. The next year marked the development

of a redesigned camshaft and another TBO

increase—to 1600 hours.

In the

mid-1970s, Piper revamped its line of metal

singles (leaving the Super Cub alone),

starting with the bottom of the PA-28 line.

The airplane that had been the Cherokee 140

became the Warrior, sporting a new,

semi-tapered wing of higher aspect ratio

than the familiar Hershey Bar. This new wing

found its way onto the Arrow in 1977,

creating the Arrow III. In that same year,

Piper made a turbocharged version of the

Arrow. The new wing improved performance

somewhat, most notably in terms of glide. It

also gave pilots a 24-gallon increase in

fuel capacity.

The Arrow III

lasted only two model years. In 1979, Piper

made a controversial design decision, opting

to equip many of its airplanes with trendy,

fashionable T-tails. The Arrow was no

exception, and the resulting machine was

dubbed Arrow IV. Predictably, performance

suffered. Like many T-tail airplanes, the

Arrow IV flies differently than Arrows with

conventional tail feathers. The T-tail,

depending on airspeed, is either very

effective or far less effective than a

conventional tail (which isn’t as prone to

abrupt transitions between different flying

regimes). This is due to the fact that the

stabilator sits up out of the propwash, and

so is less effective at low airspeeds. Many

pilots complain that the Arrow IV has odd

low-speed performance, with a tendency to

over-rotate on takeoff. Others, who don’t

try to fly the Arrow IV like the earlier

models, look more favourably upon the

T-tail. Performance can also be variable

depending on how much fertilizer the

resident birds have left on top!

As a result of

the general aviation slump, the normally

aspirated Arrow IV was not built for a few

years, from 1984 through 1988. In 1989, 27

were delivered. In 1990, Piper finally

dropped the T-tail and went back to the

conventional arrangement. Eight were built

that year, none in 1991, six in 1992, and

only one in 1994. This was also the time

when Piper was on the rocks, and searching

for a buyer.

When Piper

emerged from bankruptcy several years ago,

the Arrow was promptly back in production.

It’s essentially the same airplane as the

conventional-tail Arrow IV, with a 2001 base

price of $249,700, which includes a good

instrument package but no autopilot.

Performance/handling

The Arrow cruises at 130 to 143 knots, while

consuming nine to 12 gallons per hour. A

Cessna Cardinal RG or Grumman Tiger will go

as fast, while burning less fuel. And a

Mooney 201, on the same fuel, goes the

fastest. Still, the Arrow has a roomier

interior than all but the Cardinal, and its

useful load is the greatest: 1,200 pounds.

The first two

Arrows had somewhat limited range, thanks to

their 48-gallon fuel capacity. But the Arrow

III’s 72-gallon fuel tanks eliminated that

problem. Arrow III owners report

six-and-a-half hours of endurance, while

Arrow II owners sometimes wish for larger

tanks.

The Arrow

handles much like any PA-28, which is to say

it’s fairly benign. Stalls are a non-event,

which is in contrast to airplanes like the

Mooney; the latter will reward a slightly

off-centre ball with a sharp wing drop. The

wing loading is lower than

higher-performance retractables like the

Bonanza/Debonair and Mooney, which means a

less solid ride in turbulence and lower

speeds. However, that’s also a benefit

during landing. Owners report few vices.

Climb

performance is competent, but unremarkable.

The Arrow is not a STOL airplane, but it

doesn’t eat up runway, either.

During

letdowns, the Arrow’s gear serves as an

effective speed brake. The gear extension

limit is close to the cruise speed (which

really says more about the cruise speed than

it does about the gear), so descents aren’t

the problem they are in slick airplanes like

the Mooney.