Luscombe

150hp

by

Budd Davisson, courtesy of

www.airbum.com

No

Airplane Should be This Perfect!

Back in 1937

there seemed to be some unwritten rule that

sheet metal was something used only for

bombers, fighters and those Lear Jet

ancestors such as Spartan Executives that

used Pratt & Whitney's in the nose. It was

almost never used in little airplanes . . .

well, almost never, anyway. There was this

Don Luscombe fellow that insisted on

building those marvellous little two-place

high-wing machines that borrowed heavily on

the mystique and the materials of the big

boys.

The first metal

midget to bear the Luscombe name was the

almost-extinct, but still-legendary, Phantom

which had lines and a round engine which

made it look like a Lockheed Vega that had

been run through the fast-dry cycle and

shrunk two sizes. Not too many folks know

about the Phantom today but Luscombe's

second design, the lovely little 8 Series,

always comes up when the conversation turns

to airplanes that are fast for their

horsepower, fun-to-fly and relatively cheap.

The Luscombe 8

started life in 1937 and was still being

built under various names as late as the

1950s. The production version started out as

8's with a fifty hp Continental then the

better known 8As with sixty-five horse

coffee grinders. The Luscombes worked their

way up, letter by letter, to the 8F, with

the ninety-horse Continental and optional

flaps-which brings up an interesting

question---if the 8F was the last model of

big-engine Luscombe, does that make Gene

Popma's airplane a G model?

Gene Popma of

Somerset, New Jersey, owns one of the

"other" types of Luscombes. You see, as time

went on, and thousands of Luscombes were

built, they became one of the most common

used airplanes in existence. Eventually, the

time came when an airport of the grassroots

variety wasn't worthy of the name if it

didn't have at least one derelict Luscombe

(tires flat, leaning to one side, four

families of mice living in the wings), and

two airworthy examples that, if they were

painted at all, were done with a combination

of paint rollers and spray cans. And then

there's the "other" type of Luscombes . . .

the dressed-to-kill super birds.

Luscombes

didn't make the jump into the classic

category quite as quickly as others in its

peer group, like the sophisticated Swift or

overtly practical Cessna 140 so, today, the

dichotomy between the grassroots,

around-the-patch

king-of-the-el-cheapo-flying-machines, and

the super-spiffy Naugahyde specials is

striking. Surely Gene Popma's hot-rodded 8F

custom category classic has to be leading

the way in dragging more and more of the

paint roller specials over to the side of

the paint, pamper and polish fanatics.

I'm certain

Popma doesn't consider himself to be a

fanatic. On the other hand, he's a

highly-intelligent, rational business

executive who owns two 150 horsepower

Luscombes, so he might just be perfectly

willing to label himself "fanatic" and be

damn proud of it.

Gene and I met

as flying fanatics usually do . . . on a

sunny day at an airport. Mother 'Nature had

gotten her calendar screwed up and

mistakenly gave us a Labor Day weekend with

weather right out of a Kodak ad. I had both

hands on the tail-wires of my Pitts and had

just pushed it out through the open hangar

doors when this winged block of chrome

greased onto the runway and rolled up to the

gas pumps. I could see my own reflection

from halfway across the ramp, as I walked

towards it in the natural gait of a

midwestern moth who was attracted to an

eastern flame.

By the time I

got over to the airplane the pilot and

passenger had disappeared into the terminal,

so I did several quick laps of the craft and

made a beeline after them. There is

undoubtedly a type of protocol to be used in

rousting somebody out of a rest room but in

this case a simple, "Hey-who owns that

polished Luscombe?" was enough to bring Gene

Popma out the door and headed in my

direction. It would have been terribly

disappointing had Gene been one of those

I've-got-mine-you-find-yours type of

individuals. Fortunately, Gene was as

enthusiastic about showing his airplane as I

was in looking.

Since I had

already done a quick turn around the

hyper-polished sheet metal, I headed for the

interior and found that the sheet metal was

outshone by the unexpectedly sophisticated

accoutrements of the interior . . . how many

Luscombes do you find with new Collins

Microline gear and a full IFR panel

including ADF? It was so unexpected, in

fact, that it took me a second to assimilate

everything that was on the panel, because

there was so much there that shouldn't have

been.

Gene was

pleased as a proud papa, as he took me on a

tour of the tiny cabin of his travelling

machine. He peeled back the Velcroed

bulkhead to show the extended baggage tube

that carries his golf clubs and pointed out

how the rear baggage area would accommodate

either a twenty-gallon aux tank (which

brings the total up to a whopping forty-five

gallons) or a jump seat capable of carrying

as much as 180 pounds.

As he would

point out different parts of the interior,

he would mention that "This was done after

the engine conversion" and he mentioned the

words "engine conversion" several times

before I asked him what the conversion was.

He nonchalantly (but with a sly grin) said,

"They installed a 150-horse Lycoming."

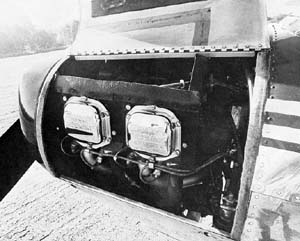

A 150 Lycoming!

I had walked around the airplane several

times and been as attentive as you could

possibly be while protecting yourself from

the awesome glare the airplane presented and

I had seen absolutely nothing that indicated

this machine was as much "go" as "show".

Even after ducking back out and looking at

the cowl for a second time, it is hard to

pick out any obvious change in form that

would set this particular Luscombe nose

apart from any others but a 150 Lycoming

very definitely sets it apart, whether it

shows or not.

It's quite

obvious that Gene is used to a certain

amount of adulation over his shiny

plaything. It's also obvious that he enjoys

every second of showing it to appreciative

audiences and I was one very appreciative

audience.

Gene, an

ex-World War Two SBD pilot, first found his

Luscombe in 1980 at an airport in Colorado.

The airplane had already been converted to a

150, but in many other ways did not measure

up to what Gene's idea of a custom classic

should be, so he took it back up to Moody

Larson in Belleville, Michigan, who did the

original conversion and bad him strip the

airplane down to its sheet metal skivvies

and bring it up again as a new airplane. It

was during this rebuild that the beautiful,

original aluminium wheel pants were

reinstalled.

Gene offered me

a pilot's-eye view of what it's like to fiy

a 150 Luscombe and I was in and had the

safety belt around me before he could

reconsider the offer.

When we lit the

burner under that Lycoming, there was no

doubt that this was not your average 8F

Luscombe. At the same time, however, there

was a "complete" feeling that this is the

way all Luscombes should be because the

panel, the interior and the noise all fit

together so smoothly. The nice thing about

taxiing Luscombes is you can see over the

nose ---maybe not quite as well as a Skyhawk,

but certainly better than most other

airplanes of their era. Of course when you

come to the end of the runway and you need

to check for traffic, the 360-degree

clearing turn is obligatory because you're

sitting so far back in the wing/ fuselage

intersection that you can't see squat out to

the side . . . one of the biggest drawbacks

in Luscombes.

Lined up on the

center line, I depressed the button on the

vernier throttle (vernier throttle in a

Luscombe!) while pushing it in and we left

out of the chute smoothly but in a hell of a

hurry. I picked the tail up almost

immediately, trying to hold a slightly

tail-down attitude so it would fly off on

its own. While I was trying to figure out

the attitude, the airplane lost its patience

with me and left the ground.

SEVENTY-FIVE TO

EIGHTY MPH WAS THE POPMA-recommended climb

speed but the nose attitude was so high that

I dropped it down and climbed out at

eighty-five or ninety, all the time turning

to see what was in front of and around me.

Even at that kind of a speed it was still

climbing at 900 to 1,000 feet a minute. Gene

has a fairly coarse prop on the airplane and

on takeoff we didn't see more than about

2300 rpm. Even so, a seventy-five mph max

climb effort puts 1,300 feet per minute on

the VSI and Gene says with a climb prop

it'll run right up to 1,900 feet per minute.

How's that for a Luscombe? But then what

would you expect with 150 horses in it?

Pushing the

nose over into level flight and screwing the

power back so the manifold pressure gauge

gave me 24 inches, I sat and watched the air

speed slowly work its way up to an indicated

cruise speed of 128 to 130 mph. It took so

long to stabilize that I would suspect that

Gene has a normal flying habit of either

leaving the power on longer, after he levels

out, or climbing a couple of hundred feet

above his altitude and then coasting down to

it to let the speed build up faster. It

really did take some time to reach a speed

that made the airplane smile.

The airplane is

equipped with one of those new Dave Clark

intercom systems that's hot all the time and

it was magnificent. At one time I took the

headset off to assess the noise level (which

is very definitely there) and found they all

but insulated you from any noise whatsoever.

They made conversation as easy as sitting in

your living room, and that might as well be

where I was sitting because there was

absolutely no similarity between sitting in

this Luscombe and any other I had flown.

Sure, the elbow-to-elbow seating position is

still there, and the same tiny little rudder

pedals placed close together, but everything

else that normally says "Luscombe" is gone

except, of course, those blinders out to the

side called wings.

I sucked the

nose up and brought the carb out as I

throttled back to do a power-off stall

series. True to Luscombe form, the stick

worked its way back into my belly and

eventually, somewhere down around forty-five

mph, the nose nodded gently and the wings

quit flying. I made a comment that that's

pretty much what I expected and Gene said,

"Try a takeoff and departure stall."

I slowed the

airplane down to around sixty, fed the power

all the way in and, at the same time,

brought the nose up and to the left, being

very careful to keep the ball in the centre.

At some number so low you couldn't read it,

the airplane quit flying and started to roll

off to the inside of the turn (maybe I

didn't have the ball centred) and was doing

so in no uncertain terms. So, yes, making a

hotrod out of a cream puff can do certain

things to its personality. Part of this

personality change can be explained by the

fact that its got enough extra weight

forward of the firewall to require nine

pounds of lead in the tail to keep the cg

even close. That extra power also allows you

to hang the nose up in the air so much

higher and so much longer that, when it

finally does pay off, it's at an angle a

stock Luscombe could never hope to match.

Interestingly

enough, the control response on the airplane

was slightly different than the normal

Luscombe. Luscombes have never been known to

have slippery, super-quick ailerons but

those on Gene's airplane were a little

heavier than normal. Since we're running

along at speeds easily twenty miles an hour

over the normal Luscombe, part of the extra

aileron force could be nothing more than

increased air loads. The rudder, however,

still lacks feeling, a trait that some give

as the reason for the Luscombe reputation as

being a little more difficult to handle on

the runway than most tail-draggers. Their

ground handling is actually no worse; it's

just that the rudder has so little feel and

the pedals have such a short throw, that it

is very easy to over-control on

rollout-something I always call upon my own

mental CRT before I turn final in a Luscombe.

ALL THROUGH THE

PATTERN, ESPECIALLY ON Final, I was reminded

what a floater Luscombes can be. Those long,

highly-effective wings let you come down

final in the neighbourhood of seventy to

seventy-five mph and glide forever. Even

though I knew this, I still had to come down

final bent a bit sideways to slip off excess

altitude. I had spent the preceding couple

of days trying to get back into shape in my

own airplane (forty-seven landings in three

days in a Pitts Special!), and my mind was

still running at Pitts speed, which is Warp

9 compared to the Luscombe's dog trot. It

was a smooth, windless day, and I felt as if

we were swimming our way through perfectly

clear molasses and slow motion was the best

we could do.

A slow motion,

three-dimensional waltz brought us down to

the centre line with only minor adjustments

from the flight deck. Incidentally, when

trimming, I found the crank-type elevator

trim, which is mounted on the front edge of

the seat between the tightly-packed butts,

to be just a little awkward to use-only

because the blubber-limited access.

As we floated

down towards the approach end of the runway,

I began bleeding off speed and rounded out

about two feet high, with the intention of

holding it off as long as it would stay up,

which is exactly what I did. I made a

beautiful landing about a foot in the air

and subjected this polished aluminium

sculpture to the indignity of a

much-less-than-perfect landing. I seemed to

be more upset about it than the airplane

was-she rolled out nice and straight on the

grass with gentle nudges from me one way or

the other to keep her nose where it should

be. I'd flown Luscombes enough on pavement

to know that they're sometimes not quite as

well behaved on hard surfaces, although they

are only marginally quicker than a Cessna

1201140. With those long wings, however, a

gusty crosswind can keep you busy.

It was late in

the evening when I watched Gene head out

over the horizon for home and the sun was

playing games with the color of his

airplane. As the airplane and the sun worked

towards their respective horizons, the

machine would be silver one minute and then

shift into a subtle gold, then flow into a

pewter-textured honey that made the airplane

appear as if any second it would melt and

return to the tranquil pool of molten metal

whence it sprang. Gene calls his airplane

the Silver Centaur and it's a perfect name

for what amounts to as nearly a perfect

airplane as you're likely to run across.

|